Parsing Between-ness: Love, Looking Backward and Forward, in Charlotte Mew’s Short Fiction from the Fin-de-Siecle.

Charlotte Mew’s body of work exists temporally, generically, and conceptually at crossroads; the British writer’s career, as both poet and fiction writer, spans the Victorian and Modern periods, and her protagonists/speakers often mirror Mew’s own state of betweenness in their struggles with mortality and embodiment, memory and myth, and the status of love in fin-de-siècle society. In this essay, I turn to her ignored fictional works in order to unpack their relative critical neglect by analyzing the peculiar mode of “betweenness” that these stories explore. I argue that Mew’s stories, moreso than her poems, trouble a clean literary trajectory from the Victorian to the Modern era, instead of evincing an erratic relationship to time and genre in an effort to unpack the particular limitations besetting modern love.

In Re-Reading the Age of Innovation. Ed. Louise Kane. Routledge. 2022. 203-216.

Offers a feminist theory of ignorance that sheds light on the misunderstood or overlooked epistemic practices of women in literature.

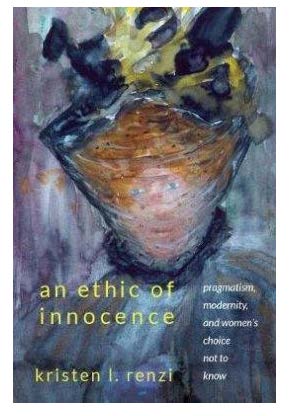

It’s with great excitement and gratitude that I announce that my first scholarly monograph, An Ethic of Innocence, will be coming out any day now (September 2019!) from SUNY Press. The book is a part of their Long Nineteenth Century series, and I couldn’t be happier with the cover they designed for me! Check out the book on their site (link via title above) and read the blurb below. You can also read an excerpt of the introduction if you go to SUNY’s site!

An Ethic of Innocence examines representations of women in American and British fin-de-siècle and modern literature who seem “not to know” things. These naïve fools, Pollyannaish dupes, obedient traditionalists, or regressive anti-feminists have been dismissed by critics as conservative, backward, and out of sync with, even threatening to, modern feminist goals. Grounded in the late nineteenth century’s changing political and generic representations of women, this book provides a novel interpretative framework for reconsidering the epistemic claims of these women. Kristen L. Renzi analyzes characters from works by Henry James, Frank Norris, Ann Petry, Rebecca West, Edith Wharton, Virginia Woolf, and others, to argue that these feminine figures who choose not to know actually represent and model crucial pragmatic strategies by which modern and contemporary subjects navigate, survive, and even oppose gender oppression.

The London Foundling Hospital's archives contain petitions that document the experiences of women who became pregnant outside of marriage and subsequently sought to give up their child to preserve their reputations. Similarities that I have uncovered in some of these narratives suggest that a serial rapist was at work in Regency-Era London. Yet to definitively pronounce on this criminal question is, I argue, impossible—not merely due to the material's cold-case status but also, and more importantly, due to the confluence of narratological and discursive issues pertaining to representations of women's sexuality in the early nineteenth century. This article identifies and discusses three key discursive dimensions that contribute to these petitions' opacity: the charitable/institutional regulations and structure, the medico-legal murkiness surrounding rape law, and the socio-cultural backdrop of "seduction." In doing so, I demonstrate how the study of these discursive dimensions, which prevent us from "solving" sex crimes from the past, allows us to unearth something of even more value: insight into the many ways in which discursive norms surrounding women's rights and sexuality—in both the nineteenth century and in the present day—work to obfuscate, rather than bring to light, gender injustice and oppression.

Feminist Formations. Vol. 30, No. 2 (2018): 118-146.

“What power did Jane Addams see in a group of elderly female Hull-House clients who came searching in 1913 for a purported “Devil Baby”? Kristen Renzi argues that Addams uses the tale as a catalyst for her depictions of cultures that explicitly challenge the modern tendency to discount the past in the name of progress. Temporally and ideologically, Addams can be situated at modernity’s threshold, for her work exhibits ties to both nineteenth-century femininity and twentieth-century public intellectualism. Through The Long Road of Woman’s Memory (1916), Addams not only overtly analyzes the ways in which women experience, remember, and give meaning to their gendered realities, but also uses the Devil-baby tale to query her own “threshold” position. Her equal investment in both modern possibilities for women and traditional, explicitly feminine forms of knowledge provides a model of considering a feminist recovery that, far from objectifying relics of the past, demonstrates the contemporary socio-political needs and possibilities that can only be understood through a pragmatic turning backward.”

In American Literary History and the Turn Toward Modernity. Eds. Melanie V. Dawson and Meredith L. Goldsmith. University of Florida Press. 2018. 144-172.

“In the Soul of the Sidereal World”: Mining Barbara Hodgson and Claudia Cohen’s The WunderCabinet for a Critical Model of Interdisciplinary Curiosity”

“This awe-inspiring essay uses the holistic experience of reading and engaging with The WunderCabinet as a model for interdisciplinary scholarship of the twenty-first century. The essay punctuates its inventive reading of The WunderCabinet with an ergodic invitation of its own—one that will allow the reader of this essay to experience some of the same choice, serendipity, association, and discovery that reading The WunderCabinet is designed to provoke in its readers.”

In Reading and Writing Experimental Texts: Critical Innovations. Eds. Kristina Quynn and Robin Silbergleid. Palgrave. 2017. 105-137.

"In the article that follows, I aim to unpack the import of this alignment between normative and grotesque modernist embodiment through a consideration of two other modern texts in which issues of identity, difference, and belonging are played out, in key scenes, via the elastic, representative material of dough: Sylvia Townsend Warner’s Lolly Willowes; or, The Loving Huntsman (1926) and Carson McCullers’s The Member of the Wedding (1946)."

Modernism/ modernity. Vol. 22, No. 1 (2015): 57-80.

"Is it better for women to be valued as subjects or as objects in the eyes of society? . . . . by posing its opening question, this piece may at first seem to query one of the key assumptions that has governed feminist theory in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. I hope, however, to show how such a question— and giving the latter, "object," as its answer—does not contradict feminist aims but rather highlights the ways in which these aims have not yet been reached."

SubStance. Vol. 42, No. 1 (2013): 120-145.

"Reading with the benefit of medical advances, as well as historical hindsight, I would like to suggest a temporary re-diagnosis of Berenice’s “unhappy malady” from the neurologically rooted epilepsy to the fluid, confusing, more psychologically inflected hysteria, for which it has often been mistaken (CW, 213). . . . This paper will use this re-diagnosis as a way to explore the means by which the female body is both set apart from and subsumed under male ideas of the body both by the character Egaeus and by critical responses to “Berenice.”From there, I will investigate the ways in which reading Berenice as a hysteric rather than an epileptic could help re-vocalize her silent figure within Egaeus’s selective narration."

ESQ: A Journal of the American Renaissance (now ESQ: A Journal of Nineteenth-Century American Literature and Culture). Vol. 58, No. 4 (2012): 601-640.

"A trans-historical Western tradition of heterosexual seeing and desiring often erects the following artistic circuit: a powerful male gaze transforms the represented female from an image of a body into an object of art by way of the topoi of statuary, surface, and stone. . . . when feminist critics argue that representations of women demean them by reducing them to "bodies," we might critique this language for its own reduction that too easily blurs the distinction between representations of female bodies and representations of female objects. In place of such blurry language, I argue that we turn to the above circuit in order to consider the female body that both this feminist reduction and this anti-feminist tradition of seeing and desiring too often displaces."

The Luminary. Issue 2: Textual Bodies (2010).